PART ONE: WHAT IS THE GREEN BELT AND WHERE DID IT COME FROM?

We’re starting a new blog series on the often controversial topic of the Green Belt.

Land with Green Belt status is highly protected from most forms of development and it’s a designation the government places great importance on.

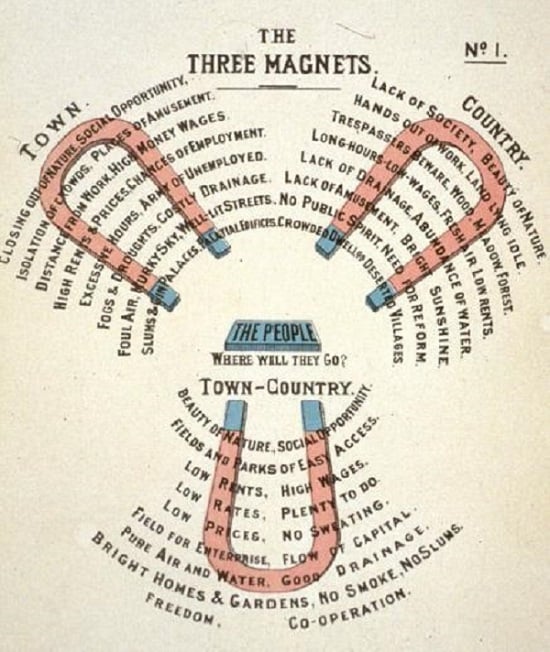

But with the nation experiencing a housing shortage crisis, is it time to take a step back and consider whether the current approach to Green Belt is helping achieve sustainable development and create places where people can, and want to, live. To quote Sir Ebenezer Howard, one of urban planning’s founding thinkers, we are asking:

‘The people. Where will they go?’

Over the next few months we’ll be considering different aspects of this complex topic, starting with asking where the concept of Green Belt land came from and what was its original purpose.

WHAT IS GREEN BELT LAND?

The Green Belt is a planning designation that identifies land around the outskirts of a city or other built up area. These swathes of land are to be protected from ‘inappropriate development’ with the intended aim to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open.

There are only a few exceptions to the definition of ‘inappropriate’ development, including but not limited to, buildings for agricultural purposes and limited infilling to address housing needs (NPPF paragraph 149).

And what of its inherent nature?

A Green Belt designation doesn’t infer any inherent ecological or recreational value. Green Belt land may be previously developed or it may be agricultural land, and it may be in private ownership, inaccessible to the public.

As former Prime Minister Teresa May said in her 2018 ‘Building a Britain fit for the future’ speech, its defining characteristic is not its beauty or its greenness, but its openness. NPPF paragraph 137 would also add, its permanence.

THE ORIGIN OF THE GREEN BELT DESIGNATION

The emergence of the Green Belt designation stems back to around the turn of the 20th century, in particular, the growing public health response to cramped living conditions arising from rapid urbanisation during and following the Industrial Revolution.

By the turn of the 20th century various public health acts had been drawn up in response to poor living conditions that were leading to serious health problems like cholera and diphtheria. The 1875 Public Health Act sought to address issues of ineffective sewerage removal and a lack of clean water supplies, problems both exasperated by significant overcrowding and slum-like living conditions.

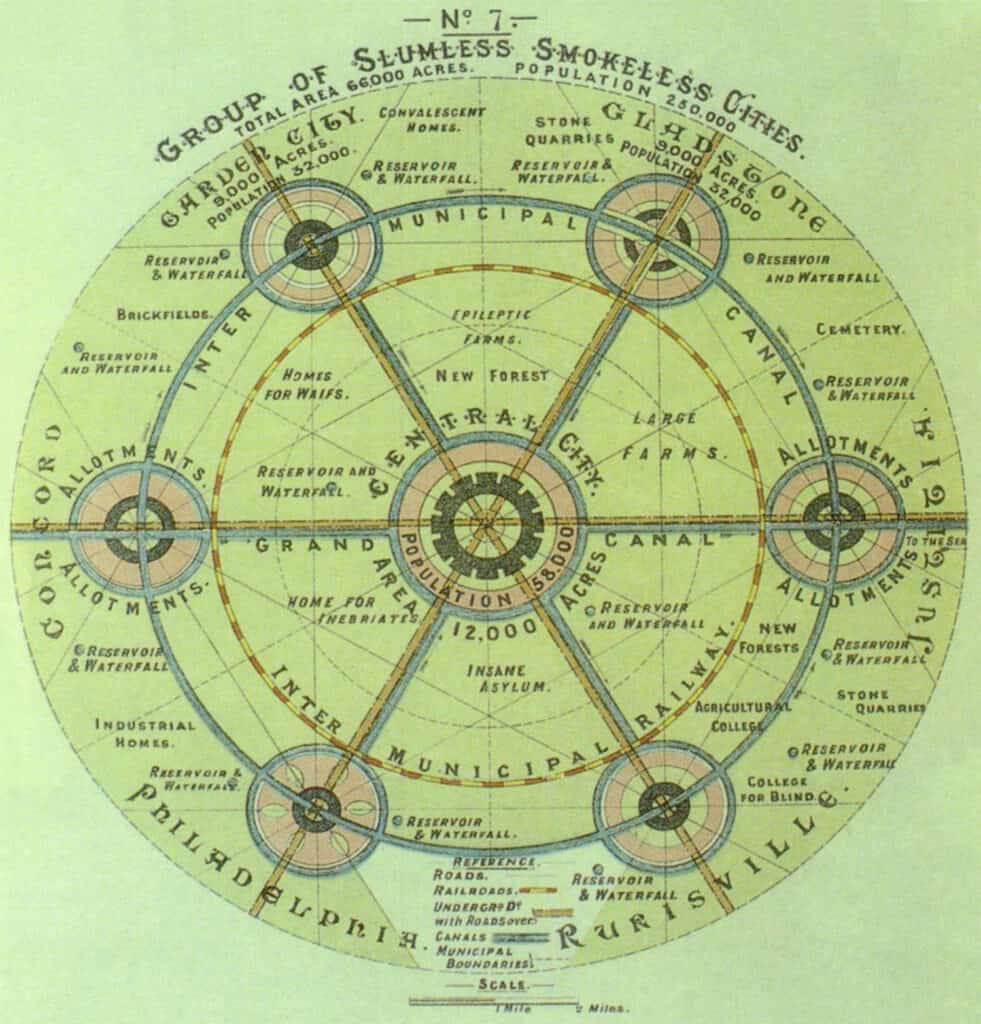

Around the same time, Sir Ebenezer Howard also sought to find a solution to the problem: by designing a new way of living that would address the social inequalities he witnessed in cities. He set out a vision of Garden Cities ‘surrounded by greenbelts’ in his influential book To-morrow: a Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898). Howard’s vision was that Garden Cities – separated from the towns by areas of protected greenbelts, would achieve the perfect balance of town and country. For him, it was the answer to the question: ‘where will the people go?’.

The 1939 Green Belt (London and Home Counties) Act enacted that Green Belts would enhance amenity ‘…in the interests of the health of the inhabitants of that country’. And by 1955 the Green Belt concept was put into policy, in Circular 42/55. Its purpose was clear. Duncan Sandys MP stated that:

‘…for the wellbeing of our people and for the preservation of the countryside, we have a clear duty to do all we can to prevent the further unrestricted sprawl of the great cities.’

The aims were two-fold: to limit unrestricted urban sprawl, and to enhance the wellbeing of people.

Two undeniably important aims that the planning system as a whole seeks to achieve, and which we wholeheartedly support.

WHY IS THE GREEN BELT SUCH AN EMOTIVE ISSUE TODAY?

As we delve deeper into the Green Belt, we’ll be asking why the topic has become so political – and so emotional.

Undoubtedly we all value the space around our homes, particularly when living in an urban environment. Indeed, that is why Howard’s vision of Garden Cities became so influential in shaping the planning policies that we know today.

Perhaps the other simple reason is that change is hard. We value open space and it is hard to see it change. Particularly if it is perceived that our own living standards will worsen for the sake of a wider societal good. Balancing potentially opposing objectives is one of the fundamental tensions that the planning system must address and it is something we are very familiar working with.

In our next blog we’ll look at one of the original aims as stated by MP Sandys: that of wellbeing. We’ll consider the relationship between Green Belt and wellbeing and ask how the planning system can best protect and enhance wellbeing.

If you have a vision for your Green Belt site, get in touch with us today and let’s see what we can do.